I think it is widely accepted that there has been some degree of power inflation through the march of D&D editions, with hit points and many other stats increasing. Ability use limitations have also decreased or gone away. For example, the humble TSR D&D magic-user or wizard got to prepare one first level spell per day, and after it was used no more spells could be cast until the next day. Compare that with the at-will magic missiles D&D Next and at-will Pathfinder cantrips.

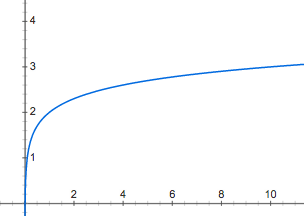

In any case, I’m not saying that any of these power curves are objectively better or anything like that (though I do personally prefer lower power games in most cases), but I thought that a graphical visualization might make it easier to communicate the ideas. Yes, in reality the power levels do not increase so linearly (for example, see how access to certain spells changes the nature of the game). But I think the general idea of the graph above, if approached abstractly, is more or less correct.

Some other notable changes are how TSR D&D has a phase shift around ninth (“name”) level, after which power accumulates more slowly (other than for magic-users, who continue to amass large numbers of spell slots). Third Edition largely did away with the phase shift, allowing hit dice and other abilities to progress until the end. Fourth Edition, chasing the “sweet spot” of levels 5 through 10 in traditional D&D, starts out much more powerful, but ends up weaker (by some comparisons).

Just as a thought, perhaps something like a logarithmic power curve would be interesting? In other words, a way to accumulate power indefinitely (this is an important motivator in the game), but at a slower and slower pace. E6 comes closest to this, but the resolution of power accumulation above sixth level is rather crude (one feat every 5000 XP), and feats also don’t model many kinds of advancement very well.

|

| Mythical ideal power curve? (Plotted with Google) |

I disagree that traditional D&D power levels off after name level for non-spellcasters. At least for Fighting Men, there are subtle and not-so-subtle mechanisms that encourage the amassing of troops. This is an increase in power, in many ways more significant than that enjoyed by spell-users.

The subject is a complex one, and is distorted by the fear of the endgame that became a part of D&D culture, but it also makes charts like this one less accurate than they could be.

To be clear, the chart is intended to reflect personal character power. I agree regarding the traditional fighter endgame, however: 1) the fighter endgame more or less went away in WotC D&D, and 2) all classes get followers (and can hire armies).

Also, just for one example, consider OD&D. Clerics get subsidized strongholds, zealot followers, and increasing spell slots.

Finally, “faithful” men will come to such a castle, being fanatically loyal, and they will serve at no cost. There will be from 10-60 heavy cavalry, 10-60 horsed crossbowmen (“Turcopole”-type), and 30-180 heavy foot.

Men & Magic, page 7.

The fighter does get exclusive access to magic swords, which increases personal power slightly relative to later editions, but I still think the comparison is valid (and becomes more valid in more recent TSR editions).

That is true, for sure. It’s part of why a lot of us argue that the Cleric was clearly overpowered from Day One. Some people (Delta, notably) just eliminate them from the game.

Yeah, the more recent editions don’t seem to have been designed by people who really understood the game (or, less charitably, didn’t care about the game). That’s fair, of course, because I can’t say that I really understood the game until relatively recently.

The desired log-curve can be had by fitting experience required per level to an exponential function (power probably something less than 2) and experience available at each level to a linear one.

The thing is, following the log example, I kind of want players to continue to accumulate smaller and smaller benefits, rather than accumulating the same size of benefit less and less frequently (if that makes sense). Using an exponential function as described results in at some point advancement essentially stopping, if I’m understanding the math right (you can advance, but the experience required is so great as to be impractical assuming that rewards are not scaling).

While Pathfinder does have a few at-will spells for casters, Magic Missile is not among them.

Thanks for the catch, you are right. I was thinking of the Ray of Frost cantrip (Pathfinder Beginner Box, Hero’s Handbook, page 28):

RAY OF FROST

RANGE 30 feet DURATION instantaneous

You fire a ray of freezing ice from your finger. Make a ranged touch attack (see page 58). If you hit, the creature takes 1d3 cold damage (roll 1d6; 1–2 means you do 1 damage, 3–4 is 2 damage, 5–6 is 3 damage).

And the “force missile” for evocation specialists (Hero’s Handbook, page 27). Not unlimited, but many more than once per day.

FORCE MISSILE 3 + INT PER DAY

You blast one opponent within 30 feet, dealing 1d4+1 points of damage. Using this ability is a standard action. You can do this a number of times per day equal to 3 + INT.

Updated the post to reflect that correction.

Clerics aren’t so overpowered when you consider they should be able to otherwise afford followers if they are tithing like they are supposed to. I think it’s a harder class to play to that level if you play it the way it needed supposed to be – limited weapons, no level 1 spell, no amassing of wealth, etc.

That should read “unable” to afford followers.

What about pointing your ideal graph the other way, so that power increases slowly for a long time then rises quickly near the end, so the top level characters are much more powerful than the ones below? Something like this: y=1/25000x^4+x

The points brought forth aside, I appreciate your post on this topic. It is a recurring issue I have between some members of my group, and a graphic of such might help in my next encounter of the topic.

About half my group is firmly for the later editions specifically for the power benefits, as it seems the game isn’t fun if they can’t keep claiming all quarter. The rest could care less what system or edition they played, and are as helpful as Switzerland. All in all it is an issue that bothers me greatly; I don’t want to be Referee for living tanks and Supermen. I’d run some Marvel game if that were the case.

Anyone else getting that?

First, I’m not sure how valid it is to compare the editions; I would argue that 1e, 3e, and 4e are all modeling different scopes of power — that is, endgame for 1e is becoming king and endgame for 3e is becoming a god. You don’t get much more apples and oranges than that.

Second, I agree with Joshua (and I guess Brendan?) in that I prefer lower powered games (and potentially slower advancement) and don’t have much interest in running a game full of tanks and supermen.

Well, characters from all editions have HP, AC, special powers, etc. It is possible to stick them in a death match arena and the systems are broadly compatible (with surprisingly little work necessary). So they are comparable in that sense.

I just picked up my copy of the 3E DMG and paged through it looking for some guidance about the endgame, and there is actually very little. The only passage I found actually seemed to say the opposite (DMG page 146, in the context of high-level play):

Players should always remember one fact: There’s always someone more powerful. You should set up your world with the idea that the PCs, while special, are not unique.

The prestige classes certainly don’t seem to suggest godhood (arcane archer, assassin, blackguard, dwarven defender, loremaster, shadowdancer). Maybe this is in a supplement?

I’m not sure about 4E (because I haven’t read much of the high level content carefully), but I think the only version of D&D that put immortality on the table explicitly was BECMI (and correspondingly the Rules Cyclopedia).

Brendan, thanks for pointing me to your article. I wish I knew about this post before I wrote my own one on the subject.

One way to achieve your mythical ideal power might be to break down each level into it’s fundamental quanta. So instead of getting level 2 at 2000XP, your saves improve at 500XP, your BAB increases at 1000XP, your HP increases at 1500XP, and you get new class abilities and spells at 2000XP. Those numbers can be rejiggered, and as you gain in level, the XP required increases cubicly while the XP gained per adventure increases quadraticly (or whatever).

You can even break down the HP into finer grains if you want, where a fighter gets +1 HP more often than a wizard gets +1 HP. That takes all the randomness out of rolling HD, though, so. . . maybe all classes get +1 HP at the same time, but clerics have a 30% chance to get +2 Hp instead and fighters have a 60% chance to get +2 HP? +30% chance for every +1 con mod (if you roll that way). That roughly preserves the average rolls from 1d4-1d6-1d8, although this results in a much narrower set of HP (lower std dev).

Those are probably two terrible ideas, but whatever.

And here’s my act of shameless self-promotion, which offers other solutions to the same problem:

http://goblinpunch.blogspot.com/2013/05/gimme-diminishing-returrns.html

Also 4th edition graph = lol.