The way Fourth Edition Dungeons & Dragons handles monster design is problematic for a game run in an old school style. There are a number of reasons for this, which I will explain below, and a few tweaks that I have come up with to make the system work better for the kind of game I am running while still working for players who are familiar with 4E rules. Hopefully, people who don’t play 4E directly may still be interested in the game design discussion.

In traditional D&D, armor class (the only defense rating) is not tied directly to level at all. A twentieth level character with no equipment and average dexterity has the same AC as a similar first level character. Characters do get harder to kill as they progress in levels (by accumulating hit points and getting better saving throws), but they don’t get inherently harder to hit.

In Fourth Edition, defenses are tied directly to level, and there are four of them (armor class, fortitude, reflex, and will). This is true for both for characters and monsters. Characters add one half of their level to each defense and monster creation guidelines also derive defenses from level rather than from concept.

This game design means that all four of the defenses have similar values for any particular monster. It results in absurdities such as high level giants having a reflex of 30 and low level pixies having a reflex of 15. What’s the point of having multiple defenses if they are all within spitting distance of each other? In general, AC will be slightly higher than the other three defenses, but (according to the 4E DMG monster creation guidelines) attacks that target AC also often have a slightly higher attack bonus! So it’s a complete wash. I actually like the concept of being able to learn about monsters and target their weaknesses, but as written 4E defenses don’t really allow that. They just end up being multiple numbers in the stat block or on the character sheet.

Here’s another problem. Hit points (both obvious and hidden in the form of healing surges) have ballooned tremendously in 4E. So players and monsters aren’t doing that much more damage, but they have a lot more hit points. This can make combat take a long time, especially if players don’t invest time in discovering the synergies between build options that allow for damage optimization.

This game design, as eloquently explained by -C over at Hack & Slash, comes from starting with the result required mechanically by the game entity (for example, a monster that is challenge rating N). Then, appropriate cosmetic details are are attached. This is what -C calls a dissociated mechanic:

Dissociated Mechanic: Result => Effect

Associated Mechanic: Effect => Result

This is also why most bestiary entries have several different “levels” of the same monster (often three: one for each tier of game play). These entries are generally not identical other than scaled numbers (the more powerful monsters will often have more abilities too), but they are close. Combined with the fact that monster defenses scale with PC attack bonuses, this means that balanced encounters are mathematically similar in all cases (this is what the 4E designers meant by “expanding the sweet spot” of D&D play). Further, because of the variance of the d20 and the level of bonuses (one-half level is a good default assumption, but in reality there will be more bonuses), we are talking about a 75% change from first to thirtieth level, which means though encounters are balanced, that balance is fragile. A little too low, and foes will be trivial. A little to high, and they will be untouchable.

Here are some of my techniques for tweaking monsters to dampen the above-mentioned dynamics without totally scrapping the system. If I’m using a monster from the monster manual, my default method is to cut the HP in half and double all damage dice (before bonuses). This makes battles of attrition less likely and also produces a credible threat. When PCs are equipped with healing surges and piles of HP, doing 1d6 or 1d8 damage is just not scary. If I use minions, I make their damage variable so that it is not obvious to the players which enemies are minions (though I have been using minions less recently; they end up just feeling like clutter).

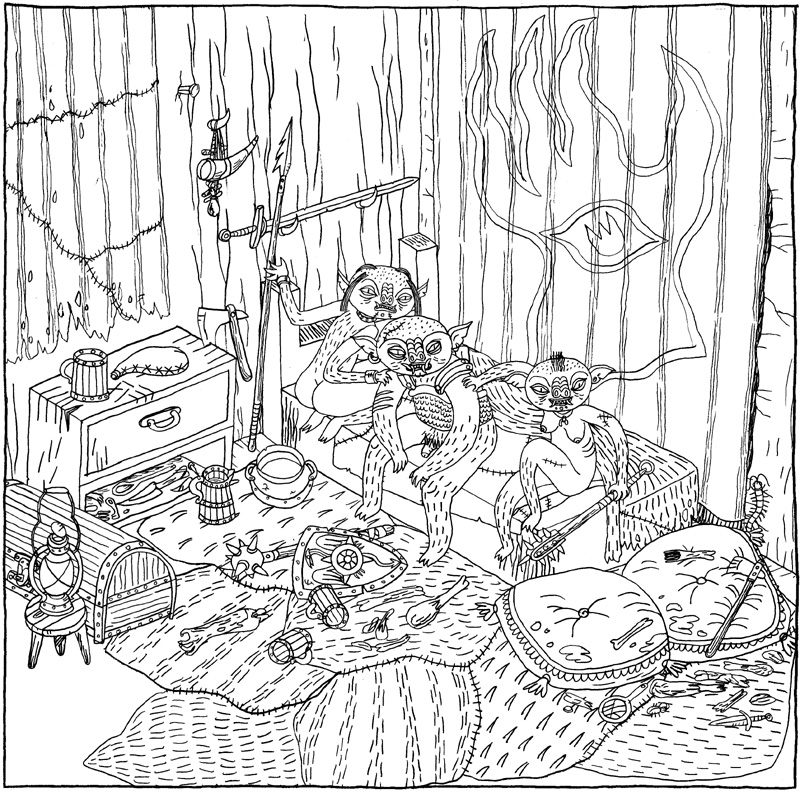

This is how I create my own monsters. Required stats for a basic monster are hit dice, AC, primary attack, secondary attack, and movement speed. I ignore the other three defenses most of the time and just use AC. I also don’t bother with ability scores or skills. Hit points are around 10 to 15 HP per hit die, depending on the monster concept (and adjusted to taste). Equipment and treasure depend on the situation. I would like to experiment with treasure tables more, but so far I have mostly just been placing treasure as I see fit (or relying on modules). XP is 100 * HD + bonus for special abilities sometimes.

AC is based on the 4E armor bonus values, which are similar to AC values in earlier editions. The values are: unarmored 10, leather 12, chain 16, plate 18, +1 or +2 for a shield, and +1 to +5 for agility. I also add a one-half hit dice bonus to keep up with the Joneses. I would like to just do away with all one-half level bonuses across the board, in the entire game, but I think that the logistics of that would be inconvenient. I’m trying to affect the player interface to the game as little as possible, as my players use the published books and the character builder program.

Thus, a 15 hit die (level) dragon would have 225 HP and a AC of 25 (18 from plate + 7 from inflation). Primary attack: claw/claw/bite +10 vs AC (2d8/2d8/2d12, each +7 for inflation). Secondary attack: breath weapon (fire): 10×10 area, 15d10 (luck throw for half damage, no hit roll required). Speed 10, fly 20. For a dragon, I might add one more special attack as well (because, you know, dragon). XP 2000 (15 * 10 + 500 for flying and fire breathing). I’m still experimenting with the relationship between hit dice and attack bonus.

Compare to the Adult Blue Dragon from the Monster Manual (page 78), which is a level 13 solo artillery monster. HP 655, AC 30, XP 4000, claw +16 vs. AC 1d6 + 6, lightning breath +18 vs. reflex 2d12 + 10 (miss is half damage). The dragon created using my house rules is easier to hit and has fewer HP, but has much more destructive attacks. This requires more planning and less direct assault, and also cuts down on the time required for combat, which is exactly what I want.