Play to find out what happens. — Vincent Baker in Apocalypse World

What does the game master or referee in a roleplaying game do? There are several different schools of thought, some of which include things like: creating challenging situations, interesting relationships, stories, and events. Whichever of these are deemed important (or forbidden), there is often a hidden assumption that the referee is the author and the people running PCs are players. Even the initialism PC suggests this (player character).

As author, the referee is expected to know what is going on. The referee is thus a kind of facilitator. They have decided beforehand about the truth of the important things (if they are a good game master in this paradigm), and these truths are expected to unfold through play, either through narration or mystery solving on the part of the players. This is independent of whether the game in question is a railroad (invalidates or circumscribes player choice) or a sandbox (respects player choice as much as is feasible given limited time and human mental capacity).

However, I haven’t been playing that way recently. I have been interested in the referee as player, not author. This is not to say that the referee does not have a special set of responsibilities or powers with respect to the setting. The ref needs to play the roles of the NPCs, run the monsters, devise traps, provide clues, adjudicate rules disputes, etc. The ref needs to know enough about the setting and scenario to do these things impartially and consistently. But they don’t need to know everything in advance. In fact, some things can be left positively up in the air (if necessary, truly uncertain things that, unforeseen, become salient during play can be determined randomly).

There is nothing wrong with a game mastering style that says the adventuring is over here (with a big neon blinking arrow pointing toward the megadungeon or whatever). It is certainly practical with regard to session prep strategy. But it seems to me that tabletop RPGs have a unique potential compared to other narrative media. They have freedom regarding not just how some questions are answered, but even what questions are important to begin with. I’ve been trying to create things that respect the logic of my setting, but also trying to let the players decide what is important. The artifacts that I create to help me run the game (monster stats, maps, NPC descriptions, calendars. etc) are tools to help me figure out what happens, not scripture regarding what makes up a fictional setting.

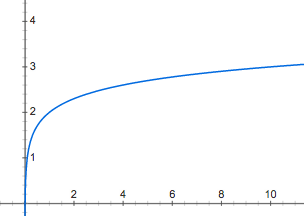

I do project events forward several steps. Making some decisions beforehand is required for impartiality. How can I discover what happens impartially if I am free to just make up whatever I want whenever I want? No, there must be some constraints. Examples: if nothing affects this area, then this NPC is going to consolidate power; this other group of NPCs is going to flee south as quickly as possible; demons attack this town during every new moon. I try to not decide things too far in advance, though. It is sort of like predicting the weather: there are too many potential variables to make forecasting far out practical. Who knows if the PCs will even be in this part of the world three months later?