Creating house rules, custom rules specific to a local group or campaign, has been common throughout the history of D&D. What makes an effective house rule or game hack and what, if anything, makes early D&D (say, pre-WotC D&D) hackable?

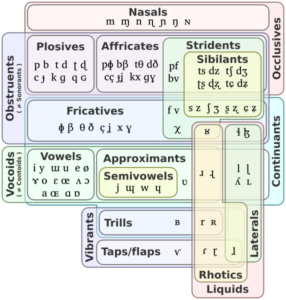

Some properties of early D&D that might contribute to this tendency include mechanical simplicity, reliance on subsystems, intuitive abstractions such as spells, classes, and monsters, avoidance of deep interrelationships between rule areas, and clear and powerful core game loops. Perversely (from the perspective of a designer, at least), some degree of roughness, inefficiency, or lack of rules clarity might also motivate house ruling. Some of the properties that contributed to hackability probably arose historically due to the gradual evolutionary nature of D&D development, but whether the properties are emergent or designed top down is irrelevant to the functional behavior.

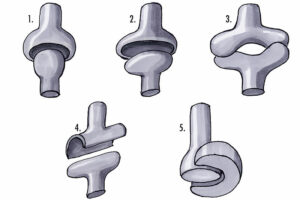

Collectively, this set of properties provides what I will call articulation points, which support both deep (structural) substitution of rules subsystems and shallow (content) addition of mechanical elements. For an example of a deep articulation point, consider the XP/advancement rules. One could swap out the treasure XP rule for something like a quest fulfillment rule. This would change the dynamics of gameplay in some ways, but would not seriously interrupt the moment to moment experience of play or the core game loop. For an example of a shallow articulation point, consider the “spell” game abstraction. One can write custom spells to replace or supplement the official spells. (Character classes are another similar shallow articulation point.)

A game is articulable to the degree that it is robust to modification in this way, providing a strong but flexible internal structure that continues to function in an understandable manner (even if the dynamics shift) when articulated both deeply and shallowly. Early D&D, especially of the “basic” variety, is particularly articulable.

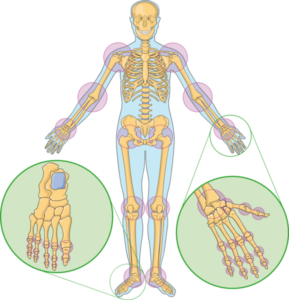

Practically speaking, one could diagram out the various deep and shallow articulation points provided by a game to guide effective house ruling. Thus, the game provides a structural chassis, much like an automobile prior to factory finishing (or modding). Additionally, and perhaps of more collective utility, mapping out a shared understanding of an underlying chassis would provide an easy way for game designers to offer custom or campaign-based “modding kits” for games while reusing existing design and minimizing wheel reinvention.

Upon consideration, such a chassis ends up being a collection of purposes that fully instantiated rules must fulfill, rather than methods or procedures for fulfilling such purposes. As such, one can think of the chassis as factoring out the teleological structure of a game. A connected mesh of whats and whys isolated or distilled from the hows.

This conceptual approach seems subtly different to me than some common previous ways of thinking about and sharing house rules. One previous approach is standardization, similar to a brand marketing or software compatibility model. One can share a new class “for” (compatible with), say, Sword & Wizardry. Or use the stat line expected for an Old School Essentials monster. Another approach is presenting the (misleading) facade of an entirely new game that has the benefit of (maybe) standing alone more effectively (that is, requiring less tacit subcultural knowledge) but has the downside of being less obviously useful as a source of articulations to other games and creating an unwarranted veneer of incompatibility for players less familiar with the subcultural history or context.

So much for the articulability of early D&D (the chassis side of the equation). What about the house rule (mod, articulation) side of the equation? A good house rule should fit into a clear articulation point, avoid spanning too many elements within the overall chassis (as this increases overall brittleness), and should be clear about whether the modification is deep (such as replacing the XP advancement subsystem or combat initiative subsystem) or shallow (adding/replacing new classes, spells, monsters, and so forth), as mixing deep and shallow creates a player interface with many special cases that need to be remembered. Probably some other things as well that I have yet to consider.

This is a great post. Implicitly that’s how I came to think about my downtime rules. I thought that there’s a sort of purpise here in a game that’s not really adequately served by existing. I definitely thought of then as occupying a space with a function in relation to the core game loop of adventuring. Anyway, I love the idea of a chassis and points of articulation.

Pingback: Teoriakatsaus #196 – ropeblogi