|

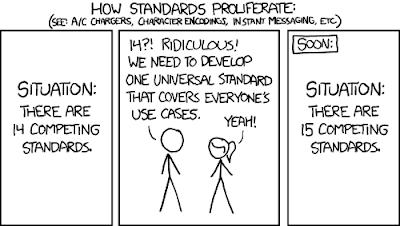

| Source: http://xkcd.com/927/ |

Monthly Archives: April 2012

Find Traps as Saving Throw

Finding traps is a saving throw, and works as such.

Thus, anyone can interact with the fictional world and discover or avoid traps purely by investigation and reason. Note that this doesn’t necessarily require any particular mechanical knowledge on the part of the referee or players (though you can go there if you want), it just requires determining trigger mechanism, effect, and clues. Remember, traps don’t need to be mechanical, or even explainable. Traps can be driven by magic, ancient technology, or incomprehensible clockwork.

I think this is really a special case of a more general principle. In some sense, all of combat is also a (complicated) saving throw. If, through smart play, a player can figure out a way to defeat or slay their enemies without a single attack roll, good for them. (Some examples: luring monsters into a trap, flooding a room, burning down a structure rather than engaging in an encounter, starting an avalanche to bury an enemy encampment, ad infinitum.)

— open locks by picking or foiling magical closures

— remove small trap devices (such as poisoned needles)

Thieves — are humans with special abilities to strike a deadly blow from behind, climb sheer surfaces, hide in shadows, filch items and pick pockets, move with stealth, listen for noises behind closed doors, pick locks and remove small traps such as poisoned needles.

AD&D Players Handbook; 1978 (page 27):

Finding/removing traps pertains to relatively small mechanical devices such as poisoned needles, spring blades, and the like. Finding is accomplished by inspection, and they are nullified by mechanical removal or by being rendered harmless.

They are the only characters who can open locks and find traps without using magic to do so. Due to these abilities, a thief is often found in a normal group of adventurers.

Find/Remove Traps: The thief is trained to find small traps and alarms. These include poisoned needles, spring blades, deadly gases, and warning bells. This skill is not effective for finding deadfall ceilings, crushing walls, or other large, mechanical traps.

You can find secret doors, simple traps, hidden compartments, and other details not readily apparent.

…

The Search skill lets a character discern some small detail or irregularity through active effort. Search does not allow you to find complex traps unless you are a rogue (see Restriction, below).

…

Restriction: While anyone can use Search to find a trap whose DC is 20 or lower, only a rogue can use Search to locate traps with higher DCs.

So this idea of find traps as a saving throw is clearly a recent innovation, but it could be thought of as a refinement of the early OD&D approach where there was no find traps ability and remove traps could only be used for very small mechanical devices. The find traps ability does not show up until AD&D. In both OD&D and AD&D, susceptible traps are very specifically defined (small devices), and this is perpetuated in 2E. Moldvay doesn’t define traps at all (perhaps leading a generation of gamers to think that hazards like the the rolling boulder of the Indiana Jones movie could be discovered and disarmed with a simple throw of the dice). And then 3E decides to do away with qualitative differentiation all together and replace it with a continuous difficulty class rating.

Empire of the Petal Throne

Empire of the Petal Throne is an RPG set in the science fantasy setting of Tékumel, inspired by an amalgam of nonwestern cultures, and based heavily on 1974 D&D. And by “based heavily on,” I mean almost identical to. Based on what I have read online, most people come to EPT for the setting, but this is actually not true for me. I am interested in the early mechanics. I first knew that I needed to read EPT when I came across the rule for re-rolling hit dice periodically (now taken to an extreme by the Carcosa dice conventions).

A PDF of a very high quality scan is available cheaply on RPGNow (around $10). Unfortunately, it has not been processed with OCR software, so it is essentially just images (i.e., one can’t copy text from it), but that being said it is very readable and much better than some of the Judge’s Guild PDFs I have bought from RPGNow. Reasonably priced hardcopy reproductions are also in print, though I have not seen them myself.

As I wrote above, the EPT rules are almost identical to OD&D, other than a strange fascination with the percentile dice. For example, the six abilities (strength, intelligence, constitution, psychic ability, dexterity, and comeliness) are rated from 1 to 100 and determined by d100 rolls (that’s right, no probability clustered around an average here). With the exception of a d100 table for inspiration, I have never been fond of using the percentile dice for mechanical resolution. So many possibilities are rarely needed. Other dice are frequently used throughout the text, so I don’t think this was a game design decision based on limiting the required dice (like the way the Storyteller system only uses the d10), so I can only conclude that Prof. Barker just really liked percentile dice.

For those that lament the pulling of the OD&D PDFs by Wizards of the Coast, just about all the original mechanics are in EPT (though, of course, none of the iconic monsters or treasures are present, and some of the terminology has been renamed). The text itself is also much better written and organized, though the writing is also extremely dense. The information about the setting is necessarily interspersed with the rules text, and as a complete newcomer to the setting, much of the information is difficult to understand. This is definitely a work that requires multiple readings.

The rulebook starts off with four and a half pages of uninterrupted two column small text that is a world overview. I made my save versus wall of text and actually made it through all of this, though most of the invented words were just processed as squiggles with the exception of common terms like Tsolyánu and Sákbe Road. I realize that some people dig on this kind of unique detail, but it does serve as a very high entry barrier for those interested in the setting or rules but not desirous of studying for an RPG setting. There are literally no common natural points of reference; the world is totally alien other than the products of civilization (e.g., there are swords, shields, spears, etc).

That being said, there are lots of interesting things to learn from this text for those interested in old school play style. Tékumel is, after all, in some sense the first published campaign setting for D&D, and one of the first sets of rules variants (I’m not sure if it came out before or after the Greyhawk and Blackmoor supplements). In fact, I would go as far as to say that EPT is one of the most interesting and valuable RPG products I have right now because it takes the spirit of OD&D and explores it prior to any precedents. And, this is a work written for adults. Not in terms of subject matter (though there are a few mature themes covered, such as slavery), but in terms of an assumed level of attention and engagement. Nothing is dumbed down. And the art is great though not plentiful. Using Tékumel as a reference for inspiration is probably more approachable than running it straight.

Though I seemed to be critical of the setting above, I’m really not. In fact, I love the ambiance. It’s just too much detail and specificity for a tabletop RPG that does not have complete buy-in and intellectual investment from all the players sitting around the table. Even if played with the expected campaign beginning (all PCs are newcomers), there would almost never be an encounter like “there are two giant wolves feasting on the carcasses of a ravaged caravan.” This is not a setting that can be played as intended casually. I do think a simplified Tékumel would be a great base for a setting, and many of the subsystems are really interesting. I’ll touch upon some more of these examples in future posts. I would also be negligent if I did not mention the excellent OD&D Discussion EPT subforum in an introductory post on EPT. So do go check that out if you are interested in Tékumel.

Cantrip Scrolls

Let’s consider the warlock and the eldritch blast ability. The warlock as a D&D class was first introduced in the 3.5 supplement Complete Arcane, and then perpetuated as a core class in the Fourth Edition Player’s Handbook. This is notable because it is one of the first appearances of a class with at-will spell-like powers. Other than the blast ability, the warlock is basically a slightly tougher magic-user with a more custom spell list (though the spells are called invocations).

In the original game, all weapons did 1d6 damage. Thus, a magic-user with a bandolier of daggers is not all that different mechanically from an eldritch blasting warlock. The major difference is that the warlock cannot be disarmed short of being restrained and has theoretically infinite ammunition, whereas the dagger throwing magic user has only practically infinite ammunition (most thrown daggers can be easily recovered after battle) and can be more obviously disarmed. A warlock’s eldritch blast might also be able to damage monsters which can only be harmed by magic.

Despite the fact that daggers do not generally run out, there is a sense of scarcity associated with anything that is numerically tracked on a character sheet, and this resource management is important to the feel of traditional D&D. The eldritch blast does not break the game mechanically, but it does break the game thematically.

What if we wanted to provide an alternative to the dagger mage with slightly more arcane flavor but that avoids the thematic problems described above. Enter the cantrip scroll. Any magic-user can create a cantrip scroll. It takes one day of work and 1 GP worth of supplies. Cantrip scrolls function just like other scrolls (they take a full round to intone, do not allow movement, and are consumed when used). The alternative to the eldritch blast is the malign ray: enemy must save versus magic or take one die of damage, range as thrown dagger.

There could also be cantrip scrolls with other functions. I prefer to think of arcane magic as inherently chaotic (following the lead of LotFP), so I don’t think they should have more constructive abilities; they should be limited to minor effects consistent with an agent of chaos.

This post began in my head as an old school take on the eldritch blast. To be honest, there wasn’t really a problem to be solved (I actually quite enjoy playing the traditional magic-user with no at-will powers and only one slot for a prepared spell at first level). I was just sitting in the dentist’s chair with nothing else to do and got to thinking: how is this at-will power really any different than a magic-user with a bag of daggers?

The Dice Know

Last night, a new player joined my weekly game for the session. I don’t know yet whether or not she will be a regular. She was completely new to tabletop RPGs and didn’t even have experience with superficially similar video games. Another player helped her create a character (she chose a human rogue) at the beginning of the game. We leaned heavily on one of the default 4E PHB rogue builds, and the process was actually relatively quick (though we didn’t really go into power descriptions or anything).

I gave the new rogue a very simple backstory to get things moving. The PCs had accepted a mission from the queen, so I made the new rogue a member of the queen’s secret police sent to assist the party. To make things interesting, I started the rogue with a free collapsible hand crossbow and six poisoned darts. No name was selected.

There were several open hooks, and the players chose the one that led to Death Frost Doom (they only know about the options via diegetic information, so they were not choosing based on knowledge of modules). When exploring the cabin her character came across the pouch of purple lotus powder. Of course the unnamed rogue decided to partake. New player, Raggi d100 table… I was kind of dreading the outcome. Percentile dice were rolled…

What was the result?

33 Character Suffers Total Amnesia!

So the character with minimal backstory (and no name) had a mind wipe. I can’t make this kind of stuff up. If the player decides to join us again, we now have a reason why she will stick with the PCs. And if she doesn’t, I now have an amnesiac member of the queen’s secret police to use as an NPC.

TV Adventuring Parties

I’m not a big fan of trying to ape other media in RPGs, especially to the extent that some games do by appropriating terminology like scenes and episodes. I’m not saying that there is nothing to be learned from other art forms, but tabletop RPGs are really their own thing, and have their own different potential. An RPG can’t do everything that a novel can do, and the reverse is also true: a tabletop RPG can do things that a novel or movie can’t.

That being said, other media can be amazingly inspirational for tabletop RPGs (hence the proliferation of “Appendix N” style lists). They can serve as examples for settings or characters. They can provide a common language. There are not that many movies, TV shows, or even books, that really capture the dynamics of a D&D party though. Even The Fellowship of the Ring, which was probably the most direct inspiration for the D&D adventuring party, doesn’t really capture it.

There are a few TV shows that come pretty close though. The ones that come immediately to mind are Lost and The Walking Dead. These two shows both feature a group of disparate characters that don’t necessarily share a common purpose, but that are thrown together and forced to cooperate in order to survive a hostile environment. Much of the story revolves around exploration, survival, and resource management. Another thing these shows share with D&D is (mostly) a lack of dependence on any single character. Characters can and do die, and the story continues.

Lost, of course, follows in a long tradition of castaway and lost world stories (Robinson Crusoe, The Lost World, Land of the Lost, etc) and I think this tradition is worth revisiting for tabletop RPG inspiration because of how well it fits structurally. I might even include the post-apocalyptic genre within the lost world genre. Can anyone think of other TV shows that fit the experience of a D&D party well?

There are two other common TV show structures which are often copied for tabletop RPGs, but usually to poor effect in my experience. The first is the “ship crew” approach (Star Trek, Farscape, Babylon 5, Battlestar Galactica, SeaQuest DSV, Stargate, Firefly, etc). The second is the “department” (or police procedural) approach (X-Files, Fringe, Law & Order, any legal or police drama you can name). These setups are commonly used for genre shows, and so are often inspiration for fantasy and sci-fi games. The department structure works particularly well for episodic presentation because each show can be a self-contained case with beginning, middle, and end. Thus, people can follow the characters over episodes if they want, but don’t really need to start from the beginning of the series to follow an individual episode.

The dependence of the ship crew approach on specific characters makes it an awkward fit with open-ended scenarios. Such a show can’t really survive the loss of too many characters, as generally the meat of the show is the soap opera interaction of the characters, not the plot or setting (some people might disagree with me here, but I stand by the point, even for shows like Star Trek). How long would any Star Trek (or clone show) last if the characters started to drop like flies? One thing that can be profitably learned from the department approach though is starting and ending at the same place, thus making shows (sessions) self-contained. This is very similar to the “start and end at the tavern” trope of much traditional play.

Dragonlance

Dragonlance occupies several strange and important places in my gaming history. It was, I think, my original introduction to D&D. I was browsing in a Waldenbooks or some store like it in a mall with my parents and I came across the book Kaz the Minotaur. I’m not sure exactly what about that book caught my attention. Perhaps it was the stone dragon on the cover. When I brought it to my parents, they wouldn’t buy it for me because it was Heroes II, volume 1. They thought I should begin with Heroes I. So I ended up walking out of the store with The Legend of Huma instead (which, in retrospect, is a better novel). I was around 10 at the time. After that, I began to devour other Dragonlance books, including the main two trilogies (The Chronicles & The Legends).

There are actually a number of elements I like in the Dragonlance setting. For example, the three orders of magic, and how magic is tied to the moons. I have borrowed the institutions of the wizards of high sorcery for several of my own settings. The basic idea is that magic is considered too dangerous for individuals to do as they please with. Instead, a monopolistic organization arose to self-regulate wizards. Upon reaching third level (in game terms) a wizard must take “the test” which controls entry into the the three orders (white, red, and black robes, corresponding to the three moons, three gods of magic, and three alignments). Presumably, this test also would allow the order to screen out the truly psychopathic or insane. Any wizard that does not take the test and join one of the orders is hunted down as a renegade. I also like the background of the Kingpriest’s hubris and the resulting cataclysm sent by the gods to punish the mortals. I like the fact that the “immortals” D&D endgame is actually played out within the Dragonlance Legends.

Speaking of the Legends, lets talk about the Raistlin books. The Chronicles are often criticized for being warmed-over epic fantasy; rather than Sauron, there is the evil goddess Takhisis. Our band of heroes has to recover some artifacts and defeat her and her minions, thus saving the world. Rather than orcs there are draconians. Yes, that is rather derivative, but it is only the first (and less interesting) part of the story. And, the heroes are not victorious due to their valor or character. In fact, they would have failed if not for the actions of Raistlin, who only aided the companions to further his own ends. For all the poor plotting, stilted dialogue, and cliche setting elements, this story still resonates with me. It’s not about a quest to destroy a dark lord. It’s about jealousy, and lust for power, and adventure.

Raistlin was probably the first character in literature that I really identified with. I went on to read many other Weis & Hickman books, including the Death Gate Cycle, which is also flawed but still great for inspiration. What about the DL series Dragonlance modules? I never played them. The idea of playing through or running a story that I had already read was deeply unattractive to me. I rarely used modules at all back then; I developed my own settings and locations. So the “railroad” aspect of Dragonlance was not something that I absorbed.

(The staff in that picture above actually lights up. I built a penlight into the top part. It was pretty cool.) Then, there was Time of the Dragon. Check out the excellent retrospective of this boxed set over at The Mule Abides. The Time of the Dragon is a setting that details the continent of Taladas. It was, if memory serves, the first published D&D product that I owned. I didn’t have a PHB or DMG to begin with, so I needed to make up anything that wasn’t in the The Rule Book to Taladas. There were only 8 monsters detailed in the back of the Rule Book (each taking an entire page, as was the custom back in the 2E days), so those monsters showed up quite frequently in my early games. All the interior art of The Time of the Dragon is done by the fantastic Stephen Fabian, who happens to be one of my favorite fantasy artists.

The main events in the Dragonlance novels take place on the continent of Ansalon, so there are few “canon conflict” problems with running a campaign in Taladas. At least, as presented in this boxed set. I don’t know what they did with the setting in more recent products. Other than the background of the cataclysm, there are not many connections between the two continents. Like the ties between Roman and Greek mythology, the gods even have different names. There is a priestly kingdom of necromancers (Thenol), a sea of lava in the middle (Hitehkel), and a great glaciers in the north sailed by ships with blades like ice skates (the glass sailors). The only weakness of the setting is the minotaur empire which is basically just Rome, but with minotaurs. For some bizarre reason, this was the only part of Taladas that really seemed to get any support or attention from TSR.

I was just looking through this boxed set again for this post, and man is there a lot of content in there. Some highlights. There is an elevation map of a gnome citadel in the sea of fire just begging to be turned into a vertical megadungeon. Included are also several level maps, one of which is a fungus farm level. With encounter tables. There are 8.5 x 11 cardstock pages with paintings of people from various cultures, some with NPC details on the back. There is a full unkeyed dungeon map called “Tomb of the Great King.” There are schematics for gnome inventions, including hang gliders and lava guns. There is a full city map easily usable as the base of a campaign. And I am just scratching the surface. I totally did not intend this post to be gushing about Time of the Dragon, but damn. This is one high-quality product. For more photos of the stuff in this boxed set, check out this post.

I sold most of my books when I went off to university in 1999. I didn’t play much over the next few years, and almost missed the Third Edition years entirely. Between 2000 and 2009, I played one session of Shadowrun (which I hated), one session of Midnight (which was cool), and one session of Ars Magica (which was complicated and didn’t go anywhere). Some time in 2006 or 2007 I did buy a copy of the 3E core books, which I read and admired for their elegance compared to the 2E of my youth, but I never used them to play and ended up selling them.

Fast forward to some time in 2010. One of the guys in my office decided to run a Fourth Edition game. It lasted for a few months, and I played in it for the first half (eladrin warlock, if you must know). Then, in the summer of 2011, for no particular reason, I thought it might be fun to run a D&D game of my own for my office mates. I decided to use 4E as it was the most recent edition and I still was not very familiar with it. The best way to learn something is to do it, right? (This experiment turned into the Nalfeshnee Hack.) I started to follow some Fourth Edition blogs. At this point I still didn’t know Moldvay B/X or OD&D from a hole in the ground.

One site I was reading (I think it was Square Fireballs) linked to a post How Dragonlance Ruined Everything at some blog called Grognardia. Thus was I introduced to the OSR. The more I read about “old school gaming” principles, the more I saw these principles at work in my own most successful past games. And the things that I didn’t understand back then (save or die, level drain, oracular dice) did actually have an inner logic, even if the books often didn’t do a good job at communicating that logic. Within the gaming community online, it seemed like all the interesting ideas, all the interesting innovation, was coming from the OSR. And so, Dragonlance has been my gateway into the realm of gaming twice now, though in dramatically different ways.

Archetypal multiclassing

While searching for something completely unrelated, I came across this system by Arcana Creations for archetypal multiclassing. One might also call it class-and-a-half multiclassing, for reasons that will become clear. It was written for Castles & Crusades, but looks usable with any similar fantasy game. The basic idea is that a multiclassed character has a primary class and a secondary class, and the secondary class is reckoned at half the level of the primary class.

There are a few brilliant ideas here. For example:

- Least restrictive weapon list but most restrictive armor list

- Experience needed for advancement: primary class + (secondary class / 2)

- Most secondary class powers only accrue at second (i.e., 2/1) level

- Limit of 2 classes helps prevent multiclassing for optimization purposes

- Average hit dice with bias toward the lower (e.g., d6 and d8 = d6)

- Fighter/magic-user is different than magic-user/fighter

It’s not explicitly stated, but I would say attack progression was take best.

Though I prefer allowing all weapons (basing damage on hit dice) and armor (but making armor penalties more salient) no matter the class, I still think the “least restrictive weapon list but most restrictive armor list” is very elegant for those limiting weapon selection by class.

Since you only really get access to the secondary class powers at second level (as first level is 1/0), there are few immediate benefits, so motivation is less likely to be power gaming. For example, a fighter/magic-user does not get to prepare any spells until second level, though they would be able to use magic items or cast from scrolls as a magic-user immediately. A first level magic-user/fighter would be able to wield any weapon though.

One variation I might try would be to roll hit dice for both classes and then divide the total by two rather than adjusting the hit die itself since I like to re-roll hit dice every adventure.

Example: Fighter/thief at level 5. With my hit die variation (and based on Moldvay hit dice), HP would be equal to (5d8 + 5d4) / 2. Minimum XP required (numbers from B/X) = 16k + (9.6k / 2) = 20.8k. Functions as a second level thief. At level 6 will function as a third level thief.

Dungeonesque Compendium

Jack over at TOTGAD has just released a free PDF compendium of his setting details and house rules. Some highlights include new classes, guidelines for running games of gothic weird fantasy, many tables (weird familiars!), and random character backgrounds. Check it out.

He has also previously written another awesome free supplement (see Flavors of Fear; link to PDF).

Save or Die Again

Here’s an idea, make save or die stuff not be instantaneous. The save and the death occur at the end of the player’s next turn. That gives everyone (including the player) a chance to do something before it happens. So, you are bitten by a giant spider and poisoned, but can chug a potion of anti-venom to give a bonus to the save at the end of your turn. It still happens quickly, so there is the sense of immediate danger, but it still gives a short time for help to prevent (or mitigate) it. Also, the image of a person rapidly turning to stone or feeling the poison spread through their body as everyone rushes to save them is incredibly dramatic.