(This is part of an ongoing discussion of the 2018 OSR Survey results. See the table of contents at the bottom of this post for links to the other parts.)

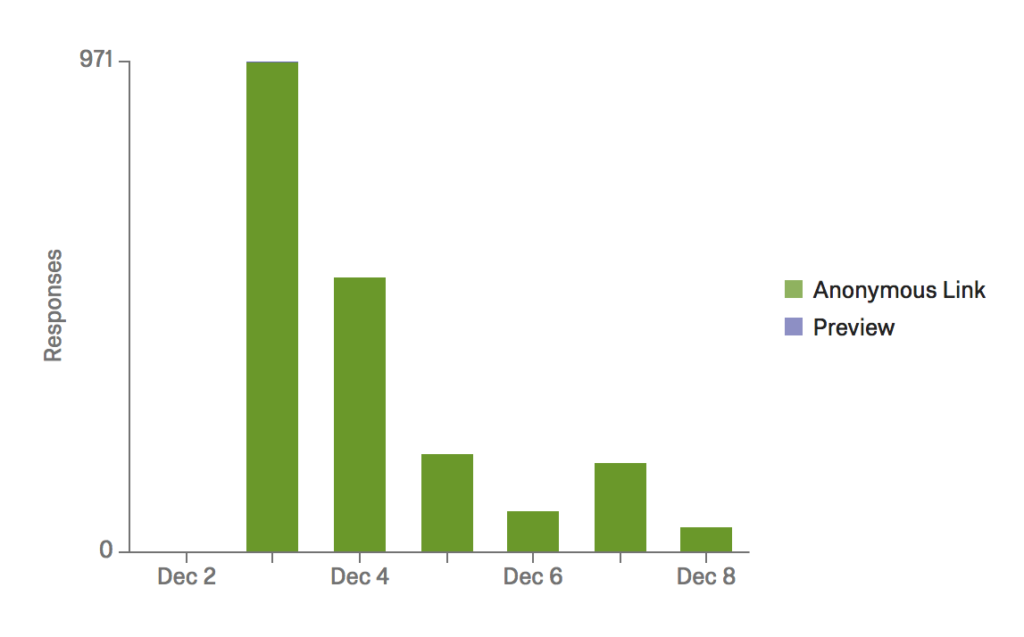

This is the first post of several where I will summarize the results of the OSR survey Ben and I ran. The survey was open from December 3rd through December 8th (2018). Given the high level of participation, and a handful of common critiques, after I have a chance to post some results I plan to ask for general feedback about how we ran the survey and what people might like to see in the future. For those who want a short summary, the TLDR of this post is that there were 2000+ responses (that is a lot), mostly from North America/Europe, and some basic demographics (such as age and country of residence) are similar for OSR participants and non-participants (based on self-categorization).

Purpose

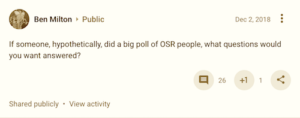

A few people asked why we were running the survey at all. The superficial (but true) answer is that I saw Ben post a question on Google Plus about what questions people might like to see on a hypothetical OSR survey. I was curious too, and I have some experience running surveys so I reached out, and here we are. The slightly more involved (and also true) answer is that I have been, over the last several years, continually surprised by seeming confusion, misunderstanding, and disagreement surrounding the meanings that people attach to the term OSR. Personally, I am primarily curious about the degree to which there is consensus about this meaning, whether the meaning differs substantially between people that consider themselves to be participating in (the?) OSR, and whether the meaning people currently see matches what they would like. Secondarily, I am also curious about what content (at the game level) people consider OSR, the geographical distribution of people that participate in (the?) OSR, and favorite OSR products. Other questions may occur to me as I proceed (and feel free to suggest questions if you have any).

A few people asked why we were running the survey at all. The superficial (but true) answer is that I saw Ben post a question on Google Plus about what questions people might like to see on a hypothetical OSR survey. I was curious too, and I have some experience running surveys so I reached out, and here we are. The slightly more involved (and also true) answer is that I have been, over the last several years, continually surprised by seeming confusion, misunderstanding, and disagreement surrounding the meanings that people attach to the term OSR. Personally, I am primarily curious about the degree to which there is consensus about this meaning, whether the meaning differs substantially between people that consider themselves to be participating in (the?) OSR, and whether the meaning people currently see matches what they would like. Secondarily, I am also curious about what content (at the game level) people consider OSR, the geographical distribution of people that participate in (the?) OSR, and favorite OSR products. Other questions may occur to me as I proceed (and feel free to suggest questions if you have any).

Responses

2018 respondents completed the survey (that serendipitous number is a coincidence). Based on some preliminary checks, I see no sign of brigading, bots, or similar threats to data quality. 134 responses failed the attention check near the end. 46 responses provided age greater than 100 and one response gave age less than 10. 9 respondents specified that I should discard their response entirely. None of these responses will contribute to my summaries. After exclusion, there were 1,828 responses. To the question Do you participate in the OSR?, 1450 respondents said Yes, 372 respondents said No, and 6 skipped the question.

Generalizability

Several people seemed suspicious about why we asked any demographic questions. The point of such questions is have some basis from which to generalize the results. For example, if respondents skew older, it would be inappropriate to assume results represent the beliefs of younger players. And so forth. Additionally, many people indicated, both to me directly and in the final “share anything” question, that they found the two items about political orientation insufficient to accurately communicate beliefs. Due to this feedback, and to ease concerns that there is some prior political agenda motivating the survey, we decided to avoid looking at those measures. Most obviously, these results speak more to the beliefs about people who talk about games online. Only people who frequent RPG forums or follow people who talk about RPGs on social media are likely to have heard about the survey at all, so that is a property of the sampling process. Put another way, we oversampled (heavily, perhaps close to exclusively) people who spend large amounts of time on hobbies online. That is, however, appropriate to OSR, which originated and developed online.

Figures

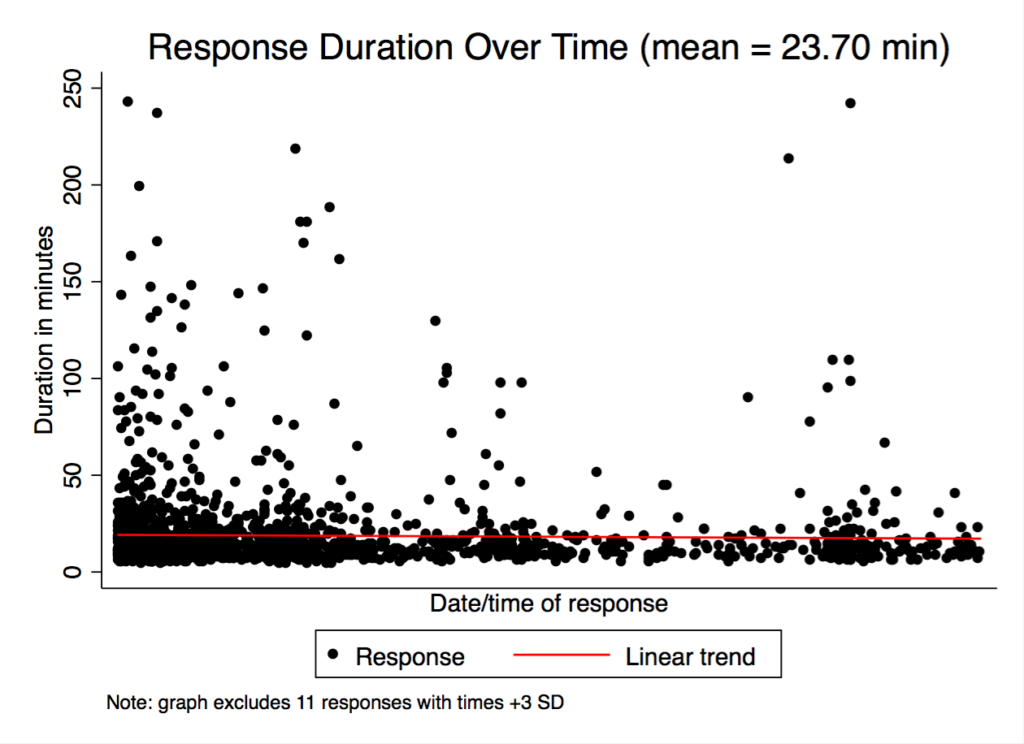

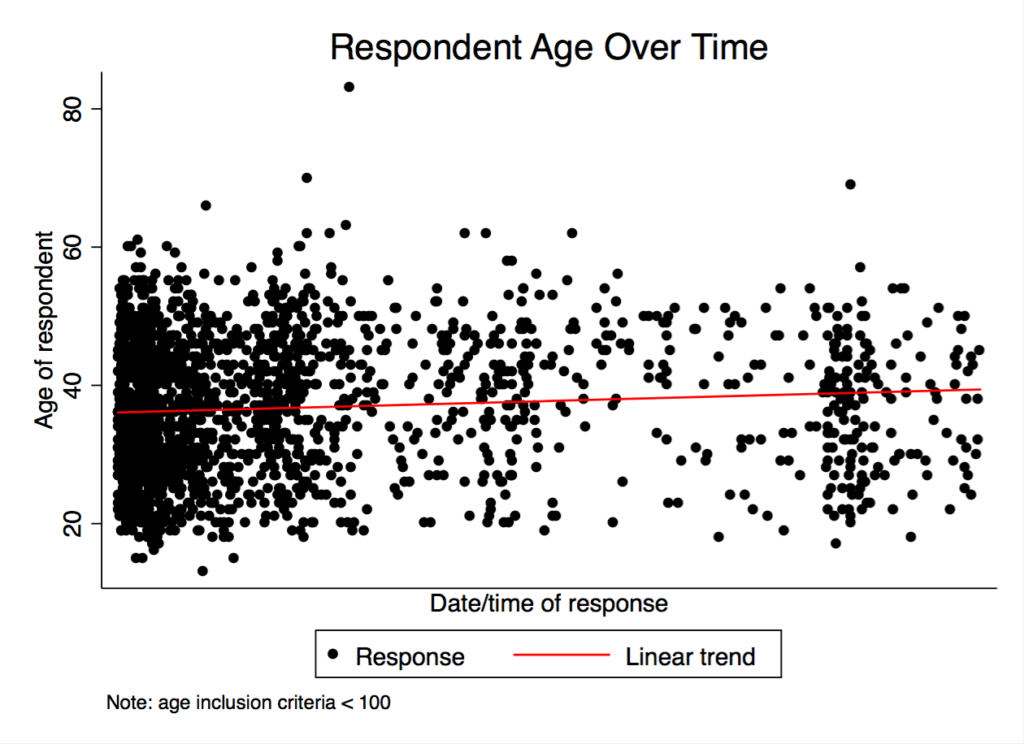

The first two figures show scatter plots of responses over time. The first plot shows how long participants took to answer the survey, in minutes. For ease of visual interpretation, I avoided plotting a handful of observations where respondents took an extra-long amount of time to submit the survey, though these responses still contribute to other results. The second plot shows respondent age, which drifts very slightly up according to the trend over time, though it is difficult to see. Plots such as these often show potential confounds or technical errors. Nothing like that jumps out at me.

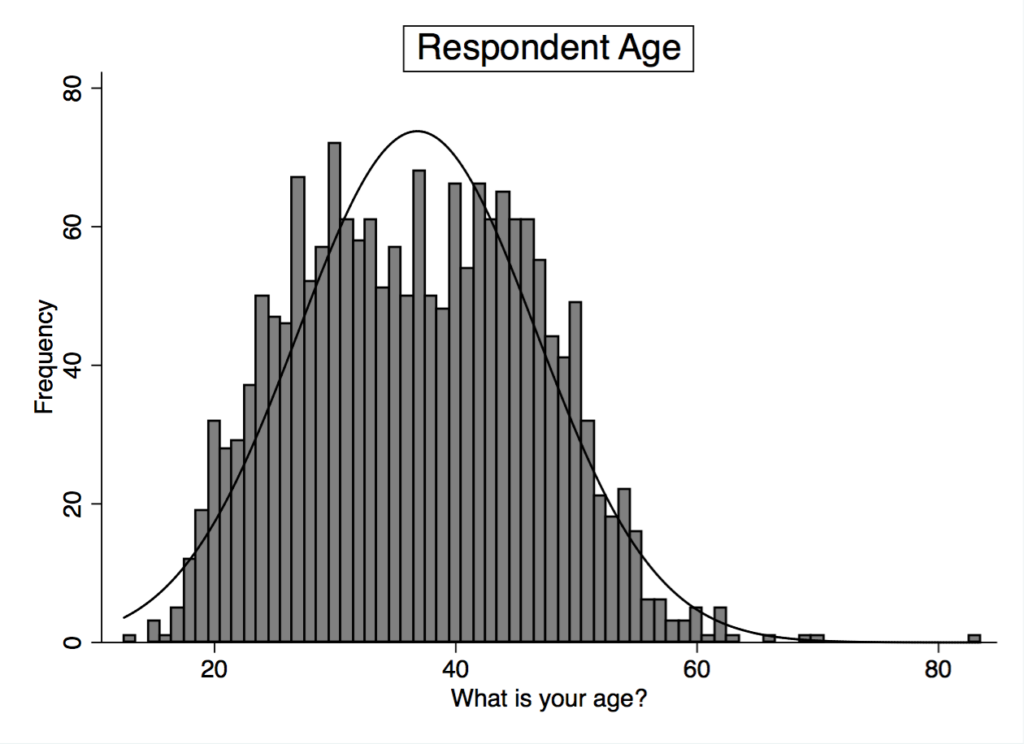

The mean response age was 36.81 (SD = 9.88, n = 1828) and the stats are similar for self-declared OSR participants (Mage = 36.58, SD = 9.87, n = 1450) and self-declared OSR non-participants (Mage = 37.64, SD = 9.90, n = 372).

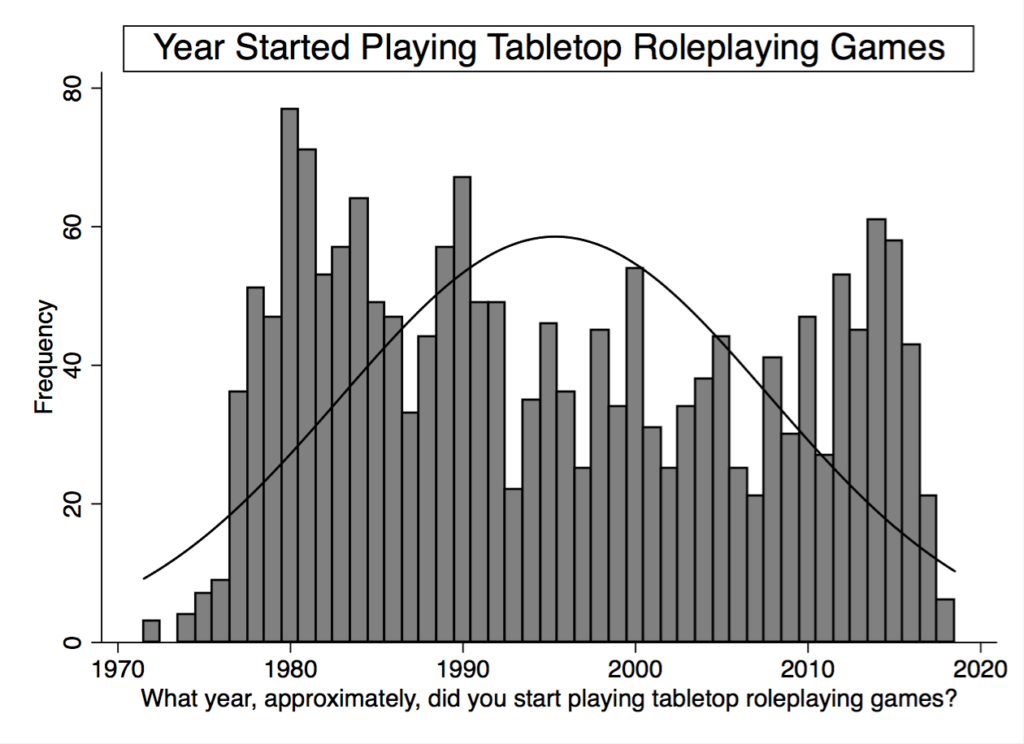

There was a mix of people that have been playing tabletop roleplaying games for a while and people that started more recently. My guess is that the frequencies by year shown below approximately reflect general industry fortunes.

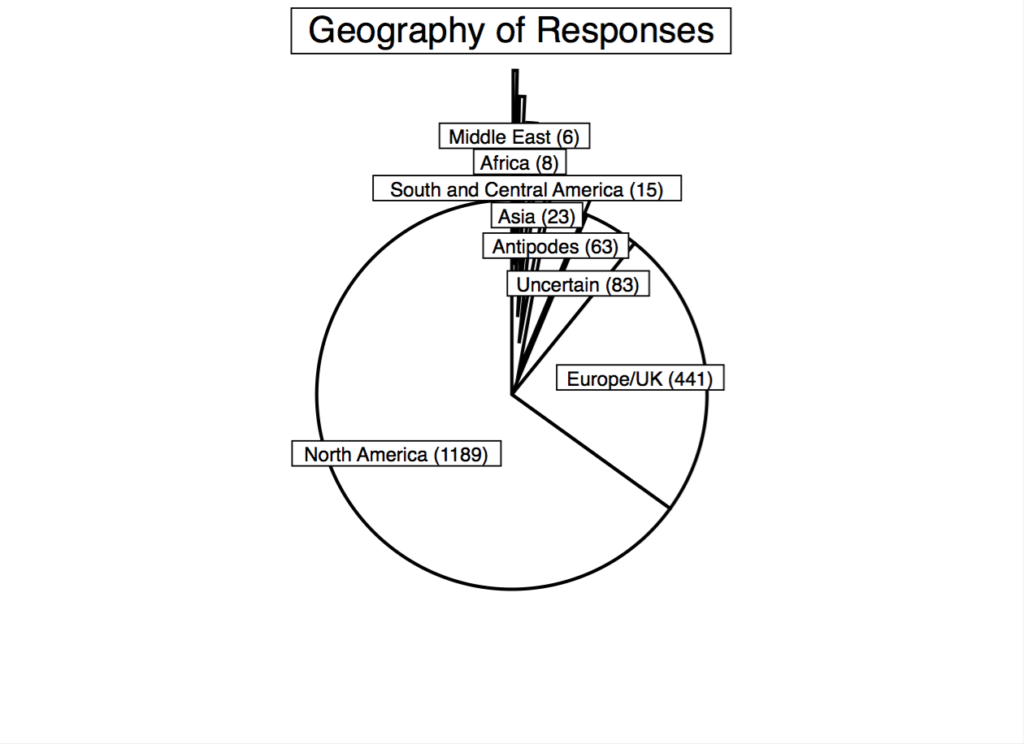

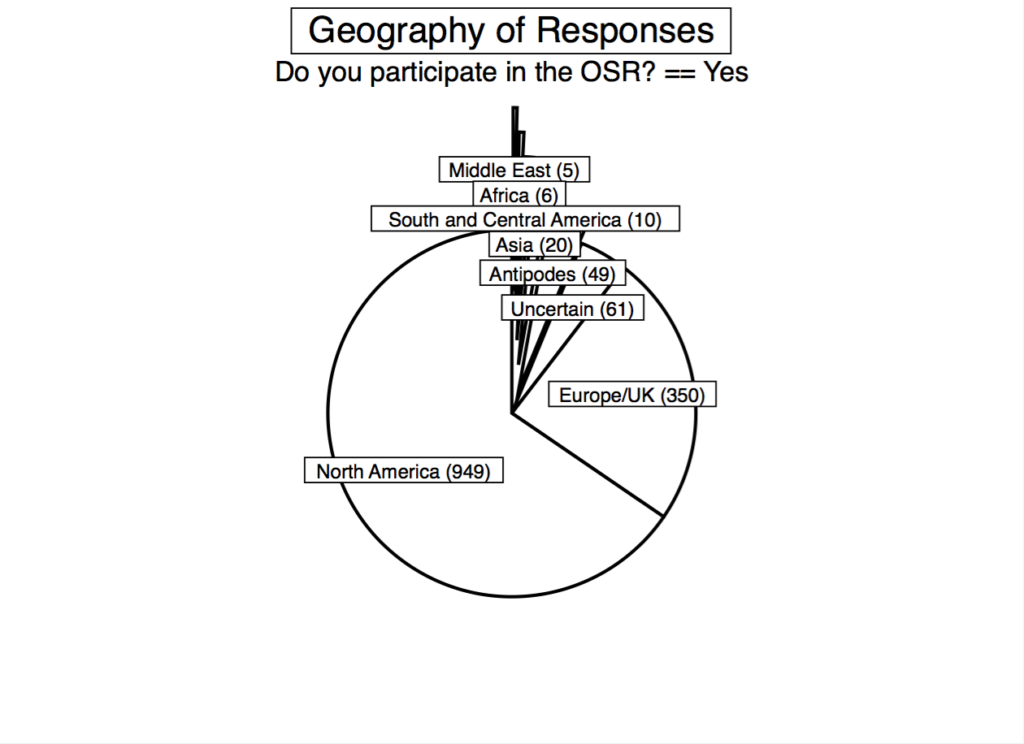

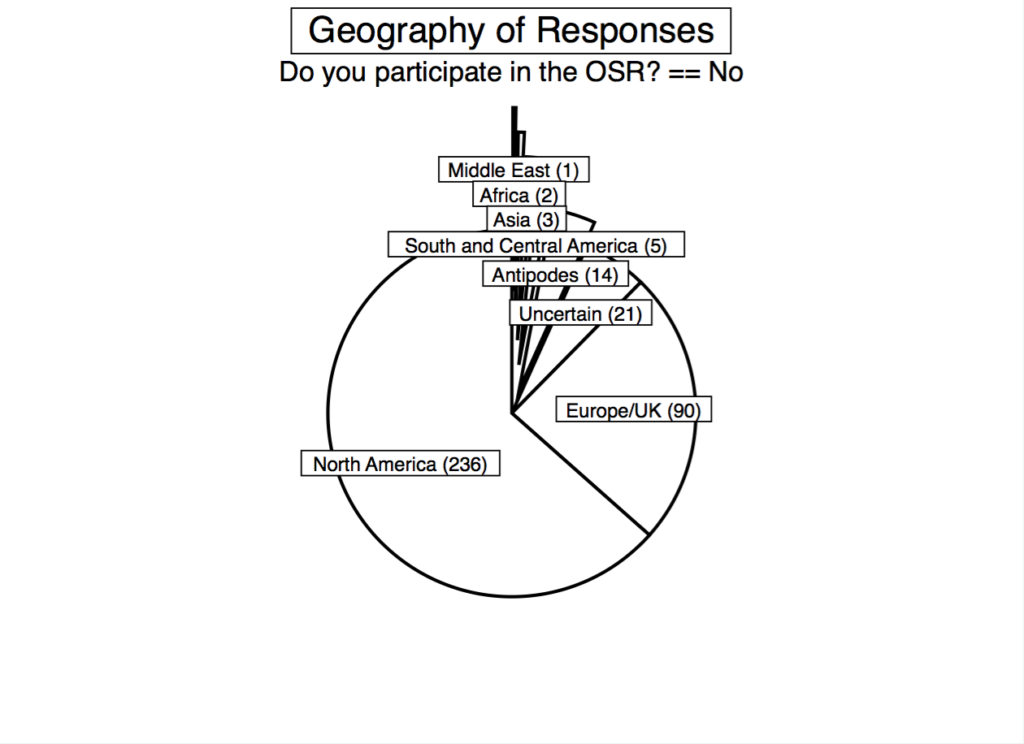

I categorized responses by rough geographic area based on country of residence. Yes, I know that “Asia” is an oversimplification, but look at the number of responses before you object. Participants that skipped the country item, or responses that were ambiguous to me, show up in the “Uncertain” category (as in, I am uncertain). The majority of responses are, unsurprisingly, from North America (65%), and 89% are from North America plus Europe combined (being relatively expansive about the definition of Europe). So when you are thinking about what kinds of conclusions you can draw from these results, keep that in mind. This survey should give a decently representative picture of people from North America and Europe who talk about tabletop roleplaying games online, but speak less to players living in other cultures.

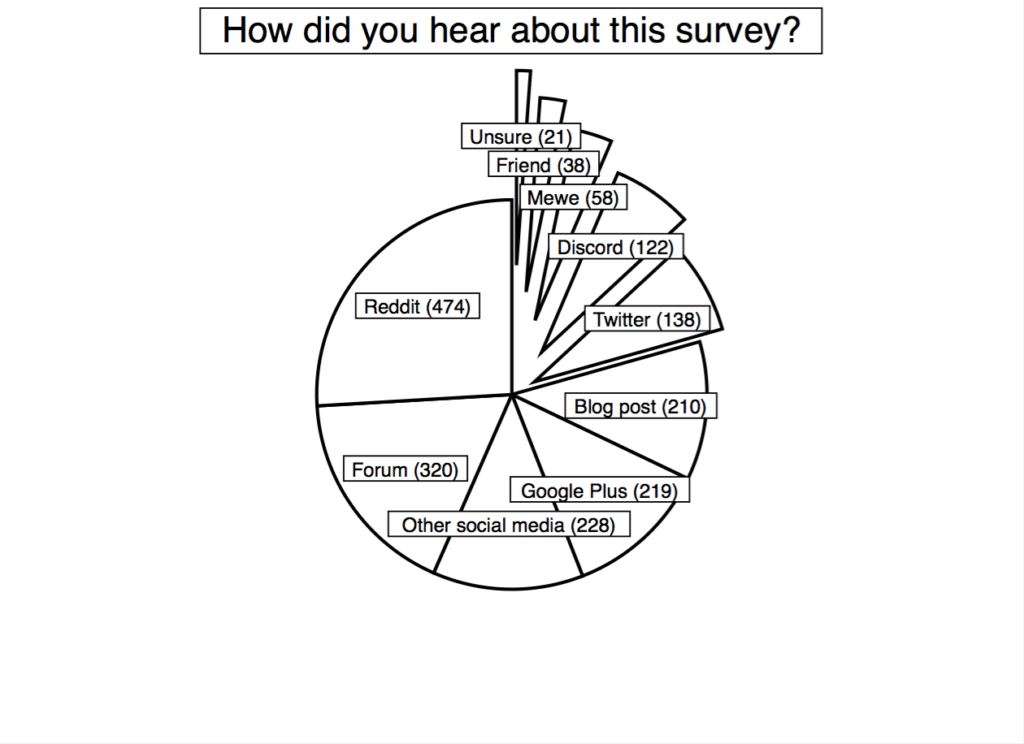

The social media context in which people reside may be even more important, for purposes of measuring beliefs about OSR, than physical geography. Respondents indicated where they heard about the survey, and that seems like a reasonable, if imperfect, proxy for social media environment. The immediate takeaway here is that Reddit is huge. The secondary takeaway is that the survey represents a much wider swath of RPG players than those that I hang around, as my crowd is mostly on Google Plus and blogs at the moment. We also asked people about how often they used various platforms for talking about games, but I think that is enough for now.